- Published at

Induction head circuits for longer sequences

In a 2-layer attention-only transformer model, an induction head can combine with an "averaging" head that stores some kind of average over the previous ~4-5 tokens to produce a circuit that can predict the next token in repeated sequences of length 2 to 5 .

Induction heads allow models to look at the sequence … [A][B] … [A] and increase the probablity of [B], or a token similar to [B], to appear next (e.g. Olsson et al., Anthropic).

The simplest picture of an induction head circuit usually consists of a “previous token head” that copies information about the previous token to the current position, followed by an “induction head” in a subsequent layer. One way to consider if/how this behaviour generalises is to consider sequences of length 3 instead of 2. For instance, in the sequence

… [A][X][B] … [C][X][D] … [A][X]

will a model predict [B] or [D] to appear next, or split the probability between them? Does it depend on the order in which they appear in the context?

Attention patterns for the triplet sequences

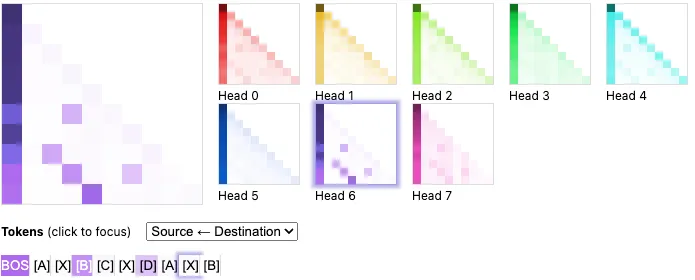

Figure 1: Attention Patterns in Layer 1 for the sequence … [A][X][B] … [C][X][D] … [A][X] discussed above.

Using the 2-layer attention-only transformer model from TransformerLens, Figure 1 below shows the attention patterns for Layer 1 given the above sequence … [A][X][B] … [C][X][D] … [A][X]. The attention patterns are averaged over 4000 batches. We can just about see from Figure 1 that the model attends more to [B] more than [C]. More quantitatively, the attention pattern at the position of the final [X] token looks like this:

Figure 2: Attention Patterns for the induction head in Layer 1 for averaged over sequences of the form … [A][X][B] … [C][X][D] … [A][X] .

In the example from Figure 2, the average probability for the next token to be [B] is 0.0649 and the average probability to be [D] is 0.0132. It’s clear that the model can correctly complete the pattern in an inductive way, looking two tokens back instead of just one. Note that if we effectively reverse the order to … [C][X][D] … [A][X][B] … [A][X] we get a similar result with a slight increase in the probability for [B]

The fact that a 2-layer transformer model can suceed in completing this triplet sequence is interesting; it implies that it’s relatively important for minimising loss, given that the model can only produce a very limited number of circuits. I wonder whether this is due to the fact that words are often tokenized into more than 2 tokens and so it’s often useful to be able to accurately complete these words later on in the context if they have appeared earlier. It could also be just due to the fact that text often repeats itself, especially in programming languages, and this is just a very useful feature to have.

Attention heads in layer 0 and positional information

To investigate the mechanism behind completing these sequences, let’s start by looking at the attention heads in Layer 0. It seems likely that one or more of these Layer 0 attention heads combines with the induction head in Layer 1 to perform the task demonstrated above. Specifically, the positional behaviour of these attention heads should be relevant. One way to visualise this is to input sequences of random tokens and calculate the average attention pattern over these sequences.

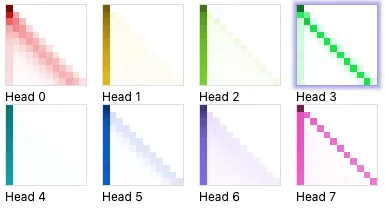

Figure 3: Attention patterns averaged over 500 random sequences of tokens.

Figure 3 shows these averaged patterns. L0H3 is the previous token head. It clearly dedicates most of its attention to the previous token, with a small amount to the present token, two tokens back and the <BOS> token. L0H0 does something similar to L0H3, but instead distributes its attention over the previous 4 - 5 tokens, peaking at two tokens back from the current token.

Figure 4: Position-only attention patterns for Layer 0 in which only the positional embeddings are input to the model.

Another way to view the positional behaviour of the Layer 0 attention heads by computing a forward pass using only the positional embeddings, without the token embeddings (Figure 4). The resulting attention patterns then clearly depend only on position, ignoring any average effect of the token embeddings. With only positional embeddings, L0H3 now attends only to the previous token, except for position 0 (that can only self-attend) and position 1 (I discuss this briefly here). L0H0 clearly attends strongly two tokens back, as well as to the previous token and more weakly to 3 tokens back. Again, there is an exception at positions 1 and 2, when attending to position 0.

Hypothesis for how the model predicts the triplet sequences

One hypothesis for explaining the triplet sequence behaviour above is that L0H0 writes information about the previous ~4-5 tokens to the residual stream, which is read by the induction head in Layer 1, as well as the previous token information written by L0H3. In addition, the query vector in the induction head probably represents not only the information “I am [X]”, but also “I follow [A]” and something like “I follow this weighted average of 4 - 5 tokens”, all of which are available in the residual stream. The key vectors probably represents both “I follow [X]” and something like “I follow this weighted average of 4 - 5 tokens”.

This hypothesis has the following consequences:

- The ability of the model to assign a higher probability to [B] over [D] in the examples above should generalise to ~4 - 5 tokens, but not much higher. This is set by how far back L0H0 can look (Figure 3). Larger models with attention heads that can look back further should be able to generalise to longer sequences.

- The ability of the model to predict the triplet sequence above should rely on the previous token head for the query vector in the induction head to operate correctly. This is because the query vector must know something about the previous token to the current token in order to compare to the information from the key vectors. The previous token head should become less important for longer sequences of 4 and 5 because now the query vector will care more about the information written by the “look back two” token to compare to the key vector.

L0H0, the “look back two” token, appears to store a weighted average of the previous 4 - 5 tokens, but this is likely not to contain information about the ordering. One can imagine finding an example where the unordered nature of the information results in a sort of an induction bug.

Testing longer sequences in the 2-layer model

Below are some results for longer sequences of the form

[A] (X X X …) [B] [C] (X X X …) [D] [A] (X X X …)

where (X X X …) denotes a sequence of tokens that could be extended arbitrarily but that I’ll limit to a length of 0 - 4 for now. Including the [A], [B], [C], [D] tokens, we produce sequences of varying from 2 to 6 in length. The table below shows the results for the probability of [B] appearing next, probabilty of [D] appearing next, the mean logit diff for [B] - [D] and whether or not the 2-layer attention-only model can predict that [B] will be more likely than [D] to appear next. The results are averaged over batches of 1000 random sequences.

| Sequence Length | P([B]) | P([D]) | Mean Logit Diff | Can Perform |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.064 | 0.001 | 6.13 | Yes |

| 3 | 0.065 | 0.013 | 2.65 | Yes |

| 4 | 0.056 | 0.029 | 1.37 | Yes |

| 5 | 0.052 | 0.044 | 0.32 | Yes |

| 6 | 0.047 | 0.049 | -0.14 | No |

To be explicit, the row with sequence length 5 implies that the model can take the following sequence

[A] [X][X][ X][ X] [B] [C] [X][X][ X][ X] [D] [A] [X][X][ X][ X]

and, on average, predict that [B] will appear next with a higher probability than [D] based on the fact the [A] token appears 4 tokens back from the current token.

One other small factor to consider is that there is an intrinsic positional dependence of the induction head that plays a small role and would slightly favour the prediction of [D] in this context, purely because it occurs later in the context relative to [B] (see this other post). Although, this factor actually makes it more difficult for the model to achieve the above pattern.

Tests with patching attention patterns

Activation patching is a technique that involves replacing the activations of a given component of a model from one forward pass with the activations from a different forward pass. If you change just one specific token between the each prompt, you can identify which components are important by how much they impact the output.

To apply activation patching, I used the above sequence as the “clean” sequence and just replaced the second [A] token with [C] for the “corrupted” sequence

[A] [X][X][ X][ X] [B] [C] [X][X][ X][ X] [D] [C] [X][X][ X][ X]

where the correct predicted token for the clean and corrupted prompts are [B] and [D] respectively. The performance metric I used here is the difference in logits for [B] and [D]. The values in Figure 5 below represent the logit difference between [B] and [D] on a scale where 0 corresponds to the logit difference for the corrupted prompt and 1 corresponds to the logit difference for the clean prompt. Attention heads that are important for the completion of the sequence will have values closer to 1, and those are less important will have values closer to 0.

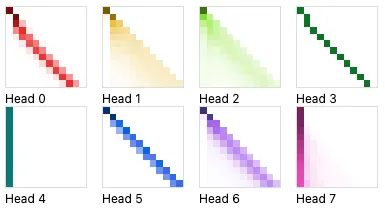

Figure 5: Results for activation patching tests by attention head for each sequence length.

Figure 5 shows the results from the activation patching for each attention head in Layers 0 and 1 for sequence lenths of 2 to 5. For all sequences, the induction head, L1H6, clearly matters a lot for the completion of the sequence. For sequences of length 3, the previous token head (L0H3) and the look-back-two head (L0H0) are important. This makes sense; the previous token head can be used by the query vector of the final token to be compared to the key vectors that read in the information written to the residual stream by the look-back-two head. For sequences of length 4 and 5, the look-back-two head is most important in Layer 0 and the previous token head becomes less important. This can be understood by considering that in sequences of 4 or 5, the query vector at the final token is no longer helped by the information written by the previous token head and instead needs to read the information written by the look-back-two head. These results support consequence #2 in the hypothesis section above.

Does the ordering matter for the look-back-two head?

The information written by the look-back-two attention head might be unordered, unless the value vector reads from both the token and positional embeddings. We can (sort of) test this by checking how the following sequence is completed:

[A] [X][X][B] [C][X][ X][D] [A][X][X][B] [C][X][ X][D] [X][A][ X]

In this sequence, [X] appears four times before the final token, twice followed by [X] and twice followed by [B]. The final two tokens [A][X] do not appear in order in the sequence, so it’s not as simple as the triplet sequence discussed above.

The model predicts [B] to appear next with a much higher probability than [X] with a logit difference of 5.61. Figure 6 shows the attention pattern for the induction head at the final token position, qualitatively consistent with the higher logit for [B] than [X]. This isn’t conclusive evidence of exactly how the look-back-two head is behaving, but appears to suggest that it’s not very sensitive to the ordering of the tokens.

Figure 6: Attention pattern in the induction head (L1H6) for the final token.

Conclusions & the look-back-two attention head

The look-back-two attention head is clearly central to successfully completing the sequences discussed in the above sections. The look-back-two attention head attends primarily two tokens back from the current token, but also to the previous token, 3 tokens back and more weakly to the current token and 4 tokens back. I describe this behaviour in a bit more detail in this other post on the previous token head.

Ultimately, I think it’s interesting that in just a 2-layer attention-only transformer, the induction head circuit generalises beyond just connecting with a previous token head to be able to repeat longer sequences. This presumably improves in-context learning.