- Published at

'Recency bias' in an induction head

The induction head in a 2-layer attention-only transformer model has a slight bias towards tokens later in the context compared to earlier. Interestingly, its notion of position appears to not depend on positional embeddings, or any specific output from an attention head in the previous layer.

Induction heads allow models to look at the sequence … [A][B] … [A] and increase the probablity of [B], or a token similar to [B], to appear next (e.g. Olsson et al., Anthropic).

One natural follow-up question to the behaviour of induction heads is ‘what happens if [A] has already appeared twice in the context, but followed by a different token each time?’ For example, would a sequence … [A][B] …[A][C] … [A] → ? predict [B] or [C] as the next token, or some probability split between [B] and [C]? Does the answer on the positions of [A][B] or [A][C] within the context?

Simple Tests

To do some tests in the direction of answering these questions, I put random sequences of the following structure through a 2-layer attention-only transformer model from the transformer_lens library:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <BOS> | R | [A] | [B] | [A] | [C] | R | R | R | R | R | R | [A] |

| <BOS> | R | [A] | [B] | R | [A] | [C] | R | R | R | R | R | [A] |

| <BOS> | R | [A] | [B] | R | R | [A] | [C] | R | R | R | R | [A] |

| <BOS> | R | [A] | [B] | R | R | R | [A] | [C] | R | R | R | [A] |

| <BOS> | R | [A] | [B] | R | R | R | R | [A] | [C] | R | R | [A] |

| <BOS> | R | [A] | [B] | R | R | R | R | R | [A] | [C] | R | [A] |

| <BOS> | R | [A] | [B] | R | R | R | R | R | R | [A] | [C] | [A] |

R indicates a random token (every R is different), and each [A] token is the same within each row. This allows us to test the impact of whether [B] or [C] is predicted at position 12 to appear next, and whether it depends on the position of the second [A] token. The results for each sequence are averaged over 2000 random samples.

Dependence on position

Figure 1: Probability of [B] and [C] tokens as a function of the position of the second [A] token, equivalent to each row in the table above.

Figure 1 shows the probability of [B] or [C] occuring next as a function of the position of the second [A] token, holding the position of the first [A] token constant. The probabilities of [B] and [C] are roughly equivalent when they are both far away from the current token (positions 4 - 7). When the second [A] token is within 4 tokens of the current token (positions 8 and later), the probability of [C] appearing next increases significantly, while the probability of [B] appearing next remains approximately the same.

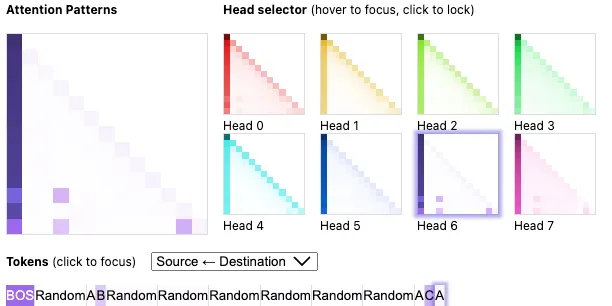

Figure 2: Attention Patterns in Layer 1 for the final row of the table above.

Figure 2 shows the Layer 1 attention patterns for the final row of the table when the second [A] token is at position 10. L1H6 is the induction head. The final [A] token attends slightly more strongly to the [C] token than the [B] token. This is consistent with the output in Figure 1 above where [C] has a higher probability than [B] when the second [A] token is at position 10.

Positional dependence of attention

We can extend the information in Figure 2 by plotting the attention patterns in the induction head for the final position in the sequence as a function of the position of the second [A] token — Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Attention Patterns in the induction head for the final position in the sequence (the third [A] token) as a function of the position of the second [A] token.

We can see clearly that the third [A] attends to [B] for all positions of the 2nd [A] token. This makes sense. It also attends to the position of [C] (one ahead of the position fo the 2nd [A] indicated in the caption). Interestingly, it has a stronger attention to [C] for positions closer to the third [A] token. This increased attention translates to a higher probability for the [C] token.

Intrinsic positional dependence

Figure 3 hints at an intrinsic positional dependence of the induction head attention patterns. One way to test this is to input random sequences of tokens and average the attention patterns produced in the induction head. This produces the following:

Figure 4: Attention Patterns in the induction head (H6) for a sequence of 7 random tokens including a <BOS> token a position 0.

The induction head tends to pay more attention to recent tokens and less attention to earlier tokens. This seems to satisfactorily explain the result in Figure 1.

Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, this recency bias seems to extend to much longer gaps in position. Figure 5 shows the same plot as Figure 4, but for 48 tokens instead of 7. Although it’s a bit noisy, the general trend still exists.

Figure 5: Attention Patterns in the induction head (H6) for a sequence of 48 random tokens including a <BOS> token a position 0.

Cause of the intrinsic positional dependence

One might imagine that the positional dependence exhibited in Figure 5 is achieved using the positional embeddings or some information written by a head in layer 0 based on the positional embeddings. However, this is not the case. The positional embeddings can be removed from the model entirely and, with random sequences of tokens, the same trend of increasing attention score can still be obtained.

Figure 6: Attention Patterns in the induction head (H6) for a sequence of 48 random tokens with only token embeddings included and all heads in layer 0 ablated except head 1.

It’s even possible to completely ablate almost any 7 of the 8 attention heads in layer 0 by setting head outputs equal to 0 and you still achieve the same trend. For instance, Figure 6 shows the attention pattern obtained when running the model with random tokens, only token embeddings and with only L0H1 activated in Layer 0. While not as smooth as Figure 5, it still exhibits the same upward trend.

So, what causes this strange positional dependence? It turns out (I think!) that this kind of positional dependence is a simple result of the fact that the magnitude of the average of different (i.e. not highly correlated) vectors depends on the number of vectors. For instance, at position 2 in the sequence the output from most of the heads in layer 0 for a sequence of random tokens will be an average of two random value vectors computed from the random tokens. Likewise at position 50, the output will also be an average of the value vectors of the tokens. However, because the value vectors are first multiplied by 1/50 and then added, the z-vector at position 50 will have a smaller magnitude than the z-vector at position 2 that results from multiplying the value vectors by only 1/2 and then adding. This behaviour is true for 7 of the 8 attention heads in Layer 0, but much weaker in L0H7 because it strongly self-attends and so you get less diminishing of the magnitude due to multiplication by a smaller factor. This might all seem obvious, but wasn’t at all obvious to me the first time realising it, so I thought I’d note it here.

Is the positional dependence intentional?

One may wonder if the positional depdendence is really intentional or helpful to the model. It certainly appears to be intrinsic to the architecture of the transformer model, which would suggest it’s not intentional. On the other hand, if the attention head really wanted to use position, it could certainly make use of the positional information written by L0H4 (the actual positional embeddings appear to be deleted by Layer 0 - I’ll discuss this in a other post). In the end, while it exists, it’s not clear how much this positional dependence affects more complex sequences of tokens.